By Brad Antoniewicz.

USB Webkeys (also known as my:keys, Intelligent Web Keys, iKeys, Internet Keys, SQUIBkeys, BuzzCards, and Bonpals) are marketing tools that you’ll commonly come across at trade shows and conferences. They come in all different shapes and sizes and, to many, these little devices are neat novelty freebees that provide a creative way for a company to market themselves. When you insert the device into the USB port of a Windows machine, a run dialog box is opened, the website of the promoter is typed before your eyes, and your default browser automatically renders the page! Pretty cool huh?

What caught my attention almost immediately when I first came across these (at Blackhat of all places) was that this is very much part of what the Teensy does!

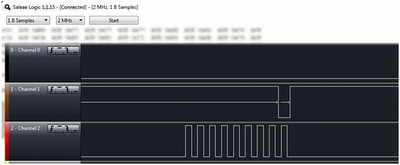

The brains of the Webkey is all stuffed into a tiny chip that fits into your USB port. If you pop that chip out of its casing and peel off the glue, you'll get something like this. The part number of this particular Webkey is "WEB-130C".

The very first thing you’ll notice on the board is the EEPROM. If you have good eyes (or a magnifying glass) you’ll see that it’s marked “J24C02C” on one line, and “DP1D07” on the next. That’s our target.

Side Rant: I’m also going out on a limb by linking RadioShack. When I was really young, I used to go to RadioShack to buy lots of stuff, particularly DTMF tone generators and 6.5535MHz crystals (for educational purposes), sometime between then and a about year ago, RadioShack lost its way and stopped selling electrical components. Over the last few months, I’ve grown to really rely on the RadioShack around the block from my office and applaud its efforts to go back to its roots by maintaining a decent hobbyist section – good job guys – selling cell phones is lame :)

You’re also going to need a fine tip for your soldering iron. This is where RadioShack is still behind – their soldering irons sort of suck when it comes to tiny electronics. I recently bought a Weller WES51 Analog Soldering Station – it is a bit pricey, but I’m convinced it’s worth it for anyone getting into hardware. I’ve also picked up some Weller tips to help get into small places and helping hands to see them.

Once you have all your hardware sorted out, solder wires to the GND (ground) and SDA (Serial Data Line) pin guesses as detailed in the next image, it might be worthwhile for you to read the rest of the article as you’ll need to do a little more soldering after this step and it is probably easier to do it all at once.

First tin the tip on your soldering iron by adding a little solder to it, then also add some solder to the EEPROM’s pins. Be careful here, too much solder will make you bridge the pins and then you’ll need to get soldering wick to clean up your mess. Next heat the pins and introduce the wire, there should be enough solder on the pins to make the connection. Avoid overheating the pins because excessive heat could damage the chip - that being said, its often surprising how much heat it can take.

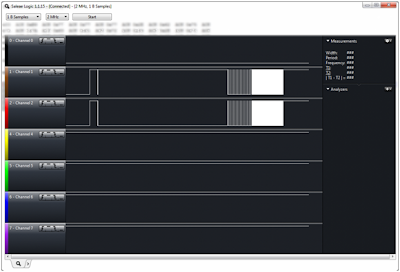

Next, we’ll need to actually plug the Webkey into our USB port so that we can see what, if any, data is going across those pins. Inserting the Webkey with the wires soldered on provides a bit of a problem given the EEPROM placement and the thickness of the board. I ended up taking the Webkey holder, bending it in half, inserting it into a USB extender, then sliding the board carefully in between the holder and the USB leads. With this secured, you can plug the USB extender’s connector into the computer as needed without needing to apply constant pressure to the Webkey to make the connection or risking messing up the joints connecting the wires and the EEPROM pins. Before connecting the USB extender to the computer, start Logic, and set it to 1 billion samples (this is a bit excessive) at 2MHz. Insert the extender into your USB port, and wait until the browser is launched. Stop Logic and let’s look at the results.

At first glance, you’ll notice that the GND (black/channel 0) is high and fluctuating, and the SDA (brown/channel 1) is pulled low. This means our initial guess that the DFN-8 pin diagram is the correct diagram for our chip is wrong – the GND should remain low. No need to worry, at least we have a good guess at our true SDA. Given its location, we can take a guess that GND is where we thought SDA was, and SDA is where we thought GND was. Also by looking at the other pin out diagrams, we can take a guess that SCL (Serial Clock) is right above SDA. Let’s solder in a wire to monitor that pin. Our new pin out diagram is:

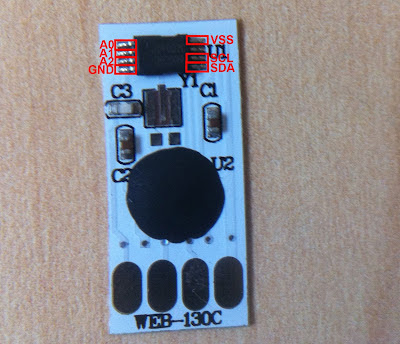

Once our SCL wire is soldered in, we’ll connect the Saleae’s red lead to our SCL guess, reassemble things, start Logic, and insert our USB extender’s connector. This time we should have Saleae Black (Channel 0) to the EEPROM's GND; Saleae Brown (Channel 1) to SDA; and Saleae Red (Channel 2) to our SCL guess. Logic’s output is as follows:

Ok, we see that the Saleae’s brown fluctuates as normal, but now the Saleae’s red also rises high and then drops low at a regular rate whenever the brown fluctuates. This is our SCL. We can see this a little clearer when we zoom in:

Next we’ll need to figure out what data is being transmitted. Let’s apply a filter within Logic to decode the I2C messages. Select the + in the rightmost pane next to “Analyzers” and choose I2C. In the new window, define SDA as “1 – ‘Channel 1’” and SCL as “2 – ‘Channel 2’”, then click “Save”.

Now under “Analyzers” you should see “I2C” listed. Click the gear icon next to it, hover over “Display using Global Settings” and change it to “Ascii & Hex”. When we zoom into a particular sequence, if the analyzer can properly decode it, it’ll display the ASCII and Hex translation.

This is what I2C looks like. We have a start sequence, then a “read” command (0xA1), followed by a response (0xD3). As we scroll right we’ll start to see the rest of data being sent.

I threw together a quick video so you can see what the entire transmission looks like:

We’ll have to do a little more soldering before we can start programming. First we’ll solder a wire into the VSS pin ,which provides power to the chip. The VSS pin location is determined by making an educated guess based on the datasheet’s pin out diagrams. The last bit of soldering is to bridge the A0, A1 and A2 pins with the GND. So in the end our pin out diagram should look like this:

After we solder everything in, it’ll look like this (which is admittedly an ugly job - and I should have removed the glue):

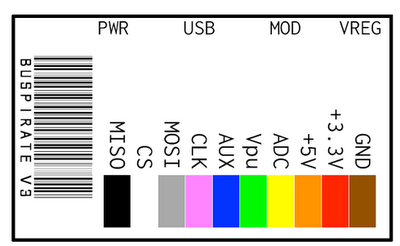

Now that we have all of the connections made, we can connect the bus pirate. The SeeedStudio Probe Kit uses the following pin outs (which is what I’ll use for the rest of this article):

Image is from http://dangerousprototypes.com/docs/Common_Bus_Pirate_cable_pinouts

Make the following connections:

These connections are all pretty straight forward with the exception of the Vpu, which is for the pullup resistors on the Bus Pirate that are needed when speaking I2C.

With the Bus Pirate connected via USB to your computer, determine the COM port it’s using then load up your terminal emulator, setting it to 115200, 8, N, 1. Since the Bus Pirate will be providing power to the EEPROM directly, there’s no need to have the Webkey connected via USB.

The Bus Pirate’s configuration commands may seem a little foreign at first but as you use them more, they become very natural and intuitive. When you connect to the Bus Pirate, hit enter to give it a little bump and you’ll be provided it’s “

First enter “

The Bus Pirate will prompt you for a speed and select “

Finally, we'll have to provide power to the EEPROM by enabling the power supplies with "

You can even issue commands on the same line, for example, to do all three just run

There's sort of an odd occurrence that happens somewhat sporadically with the Bus Pirate. Every once in awhile the SCL state will show as "

Using the Bus Pirate to read this memory is pretty simple. First we'll send an I2C "Start" using

The value provided next to the "READ" is what was actually read from the EEPROM, so here we read a

This time we got a

Now lets read all it's memory:

To figure out what's being written, we can just convert the data from hex to ASCII. Let's skip the

There we go, those bytes translate into

We'll need to do a little formatting first. We can only write 8 bytes at time, need to have the

Let's give it a whirl:

And just paste it into the Bus Pirate (make sure the Webkey isn't connected via USB):

Then turn off the Bus Pirate's power:

All done! - Here's a quick video showing the overall process:

Also, it looks like some data on the EEPROM gets cut off with longer strings. I think there is a setting in the MCU that defines how many characters it expects the URL to be- If I figure out how to reprogram the MCU, then hopefully I can change that.

Overall, these things have a big potential for a cool free Teensy-like device. They also have some seriously scarey implications if they're branded with a company logo and left in an open area like the booth of a conference.

Stay Tuned - In the next couple of months I'll be releasing a whitepaper that details the inner workings of these fun little devices even more!

What do you think? Free your mind in the comments below!

USB Webkeys (also known as my:keys, Intelligent Web Keys, iKeys, Internet Keys, SQUIBkeys, BuzzCards, and Bonpals) are marketing tools that you’ll commonly come across at trade shows and conferences. They come in all different shapes and sizes and, to many, these little devices are neat novelty freebees that provide a creative way for a company to market themselves. When you insert the device into the USB port of a Windows machine, a run dialog box is opened, the website of the promoter is typed before your eyes, and your default browser automatically renders the page! Pretty cool huh?

How it works

If you haven’t figured it out already - the Webkey mimics a USB Human Interface Device (HID). When you insert it into your USB port, your computer sees the equivalent of a USB keyboard, the Webkey “hits” the keys required to invoke the Windows run dialog box, types the URL, and presses the “enter” key.What caught my attention almost immediately when I first came across these (at Blackhat of all places) was that this is very much part of what the Teensy does!

The brains of the Webkey is all stuffed into a tiny chip that fits into your USB port. If you pop that chip out of its casing and peel off the glue, you'll get something like this. The part number of this particular Webkey is "WEB-130C".

EEPROM Fun

JJShortcut wrote up a great article describing how to reprogram the EEPROM of a specific Webkey he encountered. My Webkey is a little bit different, so first I’ll go over this same method with a little more detail and specifics with the Webkey I have.The very first thing you’ll notice on the board is the EEPROM. If you have good eyes (or a magnifying glass) you’ll see that it’s marked “J24C02C” on one line, and “DP1D07” on the next. That’s our target.

Finding the Pin Outs

If you search around the Internet for data sheets, you’ll eventually come across this one. It’s the closest I could find to the actual chip, but it doesn’t exactly match. Under ordering information, the datasheet defines how the part number (first line printed on the EEPROM) is broken down: J (Prefix), 24 (Two-wire I2C Interface), and C02 (2K bits). Unfortunately, the “C” on our chip doesn’t have a translation on the ordering information page. Based on looks (chip size and pin placement), we also get a slight hint at what the pin outs might be within the “PIN configuration” section for the DFN-8 chip, however, as you’ll soon see, it’s a bit backwards - in reality, the pin outs are more like the first three :). At any rate, this is all good news since we now have a vague idea of what we’re dealing with.Soldering In Wires

For now, we’ll blindly take the diagram for DFN-8 as the pin outs for our chip (we’ll also troubleshoot a little to show why its not). In order to interact directly with the EEPROM, we’ll have to tap into its I2C interface by soldering wires directly to the pins on the chip itself. Unless you have a lot of experience with soldering, this is tricky. The chip is small, the pins are smaller, and everything is really close together. I used 30AWG wrapping wire and .022 Solder (this is pretty big, find something smaller).Side Rant: I’m also going out on a limb by linking RadioShack. When I was really young, I used to go to RadioShack to buy lots of stuff, particularly DTMF tone generators and 6.5535MHz crystals (for educational purposes), sometime between then and a about year ago, RadioShack lost its way and stopped selling electrical components. Over the last few months, I’ve grown to really rely on the RadioShack around the block from my office and applaud its efforts to go back to its roots by maintaining a decent hobbyist section – good job guys – selling cell phones is lame :)

You’re also going to need a fine tip for your soldering iron. This is where RadioShack is still behind – their soldering irons sort of suck when it comes to tiny electronics. I recently bought a Weller WES51 Analog Soldering Station – it is a bit pricey, but I’m convinced it’s worth it for anyone getting into hardware. I’ve also picked up some Weller tips to help get into small places and helping hands to see them.

Once you have all your hardware sorted out, solder wires to the GND (ground) and SDA (Serial Data Line) pin guesses as detailed in the next image, it might be worthwhile for you to read the rest of the article as you’ll need to do a little more soldering after this step and it is probably easier to do it all at once.

First tin the tip on your soldering iron by adding a little solder to it, then also add some solder to the EEPROM’s pins. Be careful here, too much solder will make you bridge the pins and then you’ll need to get soldering wick to clean up your mess. Next heat the pins and introduce the wire, there should be enough solder on the pins to make the connection. Avoid overheating the pins because excessive heat could damage the chip - that being said, its often surprising how much heat it can take.

Figuring out The True Pin Outs

With wires connected to the two pins above, we can easily connect probes to monitor the data on the pins. We’ll use the Saleae Logic Analyzer to see what’s going on. Connect the black Saleae lead to the GND wire and the brown Saleae lead to the SDA wire.Next, we’ll need to actually plug the Webkey into our USB port so that we can see what, if any, data is going across those pins. Inserting the Webkey with the wires soldered on provides a bit of a problem given the EEPROM placement and the thickness of the board. I ended up taking the Webkey holder, bending it in half, inserting it into a USB extender, then sliding the board carefully in between the holder and the USB leads. With this secured, you can plug the USB extender’s connector into the computer as needed without needing to apply constant pressure to the Webkey to make the connection or risking messing up the joints connecting the wires and the EEPROM pins. Before connecting the USB extender to the computer, start Logic, and set it to 1 billion samples (this is a bit excessive) at 2MHz. Insert the extender into your USB port, and wait until the browser is launched. Stop Logic and let’s look at the results.

At first glance, you’ll notice that the GND (black/channel 0) is high and fluctuating, and the SDA (brown/channel 1) is pulled low. This means our initial guess that the DFN-8 pin diagram is the correct diagram for our chip is wrong – the GND should remain low. No need to worry, at least we have a good guess at our true SDA. Given its location, we can take a guess that GND is where we thought SDA was, and SDA is where we thought GND was. Also by looking at the other pin out diagrams, we can take a guess that SCL (Serial Clock) is right above SDA. Let’s solder in a wire to monitor that pin. Our new pin out diagram is:

Once our SCL wire is soldered in, we’ll connect the Saleae’s red lead to our SCL guess, reassemble things, start Logic, and insert our USB extender’s connector. This time we should have Saleae Black (Channel 0) to the EEPROM's GND; Saleae Brown (Channel 1) to SDA; and Saleae Red (Channel 2) to our SCL guess. Logic’s output is as follows:

Ok, we see that the Saleae’s brown fluctuates as normal, but now the Saleae’s red also rises high and then drops low at a regular rate whenever the brown fluctuates. This is our SCL. We can see this a little clearer when we zoom in:

Sniffing I2C Data

Now we have a pretty good chance that the Saleae’s black is actually connected to GND, brown to SDA, and red to SCL, this is all we need for I2C! For good measure, you’ll probably want to take this time to disconnect the Saleae’s black and connect Saleae’s Ground wire (which is gray) to the EEPROM's GND instead.Next we’ll need to figure out what data is being transmitted. Let’s apply a filter within Logic to decode the I2C messages. Select the + in the rightmost pane next to “Analyzers” and choose I2C. In the new window, define SDA as “1 – ‘Channel 1’” and SCL as “2 – ‘Channel 2’”, then click “Save”.

Now under “Analyzers” you should see “I2C” listed. Click the gear icon next to it, hover over “Display using Global Settings” and change it to “Ascii & Hex”. When we zoom into a particular sequence, if the analyzer can properly decode it, it’ll display the ASCII and Hex translation.

This is what I2C looks like. We have a start sequence, then a “read” command (0xA1), followed by a response (0xD3). As we scroll right we’ll start to see the rest of data being sent.

I threw together a quick video so you can see what the entire transmission looks like:

Overwriting the EEPROM

Probably the easiest method to hacking these Webkeys is to simply overwrite the EEPROM. The microcontroller looks to the EEPROM to get what it’s going to type, so if you just replace that with what you want, you’re golden. Similar to JJShortcut’s article, we’ll use the Bus Pirate to interact with the EEPROM via its I2C interface. I’m using the Bus Pirate v3.6 (Firmware v6.1 r1676 Bootloader v4.4) with the SeeedStudio Bus Pirate Probe Kit.We’ll have to do a little more soldering before we can start programming. First we’ll solder a wire into the VSS pin ,which provides power to the chip. The VSS pin location is determined by making an educated guess based on the datasheet’s pin out diagrams. The last bit of soldering is to bridge the A0, A1 and A2 pins with the GND. So in the end our pin out diagram should look like this:

After we solder everything in, it’ll look like this (which is admittedly an ugly job - and I should have removed the glue):

Now that we have all of the connections made, we can connect the bus pirate. The SeeedStudio Probe Kit uses the following pin outs (which is what I’ll use for the rest of this article):

Image is from http://dangerousprototypes.com/docs/Common_Bus_Pirate_cable_pinouts

Make the following connections:

| Bus Pirate | EEPROM | |

| MOSI | -> | SDA |

| GND | -> | GND |

| CLK | -> | SCL |

| +5V | -> | VSS |

| Vpu | -> | VSS |

These connections are all pretty straight forward with the exception of the Vpu, which is for the pullup resistors on the Bus Pirate that are needed when speaking I2C.

With the Bus Pirate connected via USB to your computer, determine the COM port it’s using then load up your terminal emulator, setting it to 115200, 8, N, 1. Since the Bus Pirate will be providing power to the EEPROM directly, there’s no need to have the Webkey connected via USB.

The Bus Pirate’s configuration commands may seem a little foreign at first but as you use them more, they become very natural and intuitive. When you connect to the Bus Pirate, hit enter to give it a little bump and you’ll be provided it’s “

HiZ>” prompt. First enter “

m” to change the mode, and select “4” for I2C. HiZ>m

1. HiZ

2. 1-WIRE

3. UART

4. I2C

5. SPI

6. 2WIRE

7. 3WIRE

8. LCD

x. exit(without change)

(1)>4

The Bus Pirate will prompt you for a speed and select “

4” for ~400KHz. Then you should be told the Bus Pirate is “Ready”. Set speed:

1. ~5KHz

2. ~50KHz

3. ~100KHz

4. ~400KHz

(1)>4

Ready

I2C>

Finally, we'll have to provide power to the EEPROM by enabling the power supplies with "

W" and the pull up resistors with "P", then finally use "v" to verify (all commands are case sensitive): I2C>W

POWER SUPPLIES ON

I2C>P

Pull-up resistors ON

I2C>v

Pinstates:

1.(BR) 2.(RD) 3.(OR) 4.(YW) 5.(GN) 6.(BL) 7.(PU) 8.(GR) 9.(WT) 0.(Blk)

GND 3.3V 5.0V ADC VPU AUX SCL SDA - -

P P P I I I I I I I

GND 3.21V 4.91V 0.00V 4.97V L H H H H

You can even issue commands on the same line, for example, to do all three just run

WPv.There's sort of an odd occurrence that happens somewhat sporadically with the Bus Pirate. Every once in awhile the SCL state will show as "

L", or low. This might happen if you have the USB connected while you're providing power via the Bus Pirate - i'm not sure, but you can kick it back into shape by disconnecting the Webkey from it's USB port, and if that doesnt work, try running the (1) macro or resetting the Bus Pirate. Reading EEPROM

The EEPROM maintains a pointer to the memory address that will be read when a read command (0xA1) is issued. The pointer increments each time there is a read. If it's pointing at the last available memory address, and a read is issued, it just wraps back around to the first available memory address. You can set the pointer to a particular location by issuing a write (0xA0) to the memory address you want to reset it to. For instance, if you wanted to reset it to address 0x00, you'd issue a 0xA0 0x00. You'll see how to do that with the Bus Pirate a little later. Using the Bus Pirate to read this memory is pretty simple. First we'll send an I2C "Start" using

[. Then we'll send a read (0xa1) command, tell the Bus Pirate to read data from the bus (r) and send an I2C "Stop" using ]. All together the command to be executed is [0xa0 r]. Let's see what that looks like: I2C>[0xa1 r]

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA1 ACK

READ: 0xD3

NACK

I2C STOP BIT

The value provided next to the "READ" is what was actually read from the EEPROM, so here we read a

0xD3. If we reissue the same request, we'll see how the pointer moved to the next memory location I2C>[0xa1 r]

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA1 ACK

READ: 0xB9

NACK

I2C STOP BIT

This time we got a

0xB9. Now if we reset the pointer to memory location 0x00 with [0xa0 0x00], we'll get that 0xD3 again: I2C>[0xa0 0x00][0xa1 r]

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA0 ACK

WRITE: 0x00 ACK

I2C STOP BIT

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA1 ACK

READ: 0xD3

NACK

I2C STOP BIT

Now lets read all it's memory:

I2C>[0xa0 0x00][0xa1 r:256]

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA0 ACK

WRITE: 0x00 ACK

I2C STOP BIT

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA1 ACK

READ: 0xD3 ACK 0xB9 ACK 0x77 ACK 0x77 ACK 0x77 ACK 0x2E ACK

0x66 ACK 0x6F ACK 0x75 ACK 0x6E ACK 0x64 ACK 0x73 ACK

0x74 ACK 0x6F ACK 0x6E ACK 0x65 ACK 0x2E ACK 0x63 ACK

0x6F ACK 0x6D ACK 0xD3 ACK 0xB9 ACK 0xA8 ACK 0x80 ACK

0x80 ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xD3 ACK 0xB9 ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK

0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF ACK 0xFF

NACK

I2C STOP BIT

I2C>

To figure out what's being written, we can just convert the data from hex to ASCII. Let's skip the

0xD3 0xB9 (Not exactly sure what these do, but things act funky if you remove them) and translate the following 18 bytes (0x77 0x77 0x77 0x2E 0x66 0x6F 0x75 0x6E 0x64 0x73 0x74 0x6F 0x6E 0x65 0x2E 0x63 0x6F 0x6D): root@bt:~# python -c "import binascii; print binascii.unhexlify('7777772E666F756E6473746f6e652e636f6d')"

www.foundstone.com

There we go, those bytes translate into

www.foundstone.com!Writing EEPROM

Ok, we can read the data, now let's write something! We'll have take whatever we want to execute and convert it to hex, here's a quick python one liner to do so, just change the "text" variable. For instance, lets start notepad, and send a little message: root@bt:~# python -c 'exec("import binascii\nimport sys\ntext=\"notepad\"\nfor letter in text:\n print \"0x\" + binascii.hexlify(letter),")'

0x6e 0x6f 0x74 0x65 0x70 0x61 0x64

root@bt:~# python -c 'exec("import binascii\nimport sys\ntext=\"ALL YOUR BASE ARE BELONG TO US!\"\nfor letter in text:\n print \"0x\" + binascii.hexlify(letter),")'

0x41 0x4c 0x4c 0x20 0x59 0x4f 0x55 0x52 0x20 0x42 0x41 0x53 0x45 0x20 0x41 0x52 0x45 0x20 0x42 0x45 0x4c 0x4f 0x4e 0x47 0x20 0x54 0x4f 0x20 0x55 0x53 0x21

We'll need to do a little formatting first. We can only write 8 bytes at time, need to have the

0xD3 0xB9 before our text, and 0x80 0x80 0x80 after. I wrote a quick script that will do the basic formatting for you: root@bt:~# cat webkey_i2c_format.py

#!/usr/bin/env python

#

# webkey_i2c_format.py -

# simple script to convert an ascii string

# into hex and prepare it for i2c writing

# using the bus pirate's commands

#

# This was made specific for the EEPROM used

# with USB Webkeys

#

# use '+' for enter

#

# -brad antoniewicz

#

import binascii

import sys

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print sys.argv[0]," - Simple bus pirate i2c formatting tool"

print "-------------------------------------------------"

print "\t+\t-\tEnter"

print "\t#\t-\tTime waster\n"

print "usage:"

print "\t",sys.argv[0]," \"notepad +##### hello from brad\" \n"

sys.exit(1)

text=sys.argv[1]

header="[0xA0 0 0xD3 0xB9"

#trailer=['0xD3', '0xB9', '0xA8', '0x80', '0x80', '0x80', '0xFF', '0xFF']

trailer=['0x80', '0x80', '0x80', '0xFF', '0xFF']

#trailer=['0xFF', '0xFF', '0xFF', '0xFF', '0xFF', '0xFF', '0xFF', '0xFF'] #0xA9 = ESC 0xA7=0 0xA1 = 4 0xB0 = ] 0xB1 = \

count=2 # To make up for the header

print header,

for letter in text:

count+=1

if letter == '+': # for enter

print "0xA8",

elif letter == "#": # for pause

print "0xFF",

else:

print "0x" + binascii.hexlify(letter),

if count % 8 == 0 :

print "][0xA0",count,

endofline=count%8

i=0

while i < len(trailer):

if endofline == 8:

print "][0xA0",

if count % 8 == 0:

print count+8,

else:

print count+8 - (count % 8),

endofline = 0;

print trailer[i],

endofline+=1

i+=1

print "][0xA0 0x00]"

Let's give it a whirl:

root@bt:~# ./webkey_i2c_format.py "notepad +##### hello from brad"

[0xA0 0 0xD3 0xB9 0x6e 0x6f 0x74 0x65 0x70 0x61 ]

[0xA0 8 0x64 0x20 0xA8 0xFF 0xFF 0xFF 0xFF 0xFF ]

[0xA0 16 0xFF 0x20 0x68 0x65 0x6c 0x6c 0x6f 0x20 ]

[0xA0 24 0x66 0x72 0x6f 0x6d 0x20 0x62 0x72 0x61 ]

[0xA0 32 0x64 0x80 0x80 0x80 0xFF 0xFF ][0xA0 0x00]

And just paste it into the Bus Pirate (make sure the Webkey isn't connected via USB):

I2C>[0xA0 0 0xD3 0xB9 0x6e 0x6f 0x74 0x65 0x70 0x61 ]

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA0 ACK

WRITE: 0x00 ACK

WRITE: 0xD3 ACK

WRITE: 0xB9 ACK

WRITE: 0x6E ACK

WRITE: 0x6F ACK

WRITE: 0x74 ACK

WRITE: 0x65 ACK

WRITE: 0x70 ACK

WRITE: 0x61 ACK

I2C STOP BIT

I2C>[0xA0 8 0x64 0x20 0xA8 0xFF 0xFF 0xFF 0xFF 0xFF ]

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA0 ACK

WRITE: 0x08 ACK

WRITE: 0x64 ACK

WRITE: 0x20 ACK

WRITE: 0xA8 ACK

WRITE: 0xFF ACK

WRITE: 0xFF ACK

WRITE: 0xFF ACK

WRITE: 0xFF ACK

WRITE: 0xFF ACK

I2C STOP BIT

I2C>[0xA0 16 0xFF 0x20 0x68 0x65 0x6c 0x6c 0x6f 0x20 ]

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA0 ACK

WRITE: 0x10 ACK

WRITE: 0xFF ACK

WRITE: 0x20 ACK

WRITE: 0x68 ACK

WRITE: 0x65 ACK

WRITE: 0x6C ACK

WRITE: 0x6C ACK

WRITE: 0x6F ACK

WRITE: 0x20 ACK

I2C STOP BIT

I2C>[0xA0 24 0x66 0x72 0x6f 0x6d 0x20 0x62 0x72 0x61 ]

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA0 ACK

WRITE: 0x18 ACK

WRITE: 0x66 ACK

WRITE: 0x72 ACK

WRITE: 0x6F ACK

WRITE: 0x6D ACK

WRITE: 0x20 ACK

WRITE: 0x62 ACK

WRITE: 0x72 ACK

WRITE: 0x61 ACK

I2C STOP BIT

I2C>[0xA0 32 0x64 0x80 0x80 0x80 0xFF 0xFF ][0xA0 0x00]

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA0 ACK

WRITE: 0x20 ACK

WRITE: 0x64 ACK

WRITE: 0x80 ACK

WRITE: 0x80 ACK

WRITE: 0x80 ACK

WRITE: 0xFF ACK

WRITE: 0xFF ACK

I2C STOP BIT

I2C START BIT

WRITE: 0xA0 ACK

WRITE: 0x00 ACK

I2C STOP BIT

I2C>

Then turn off the Bus Pirate's power:

I2C>w

POWER SUPPLIES OFF

All done! - Here's a quick video showing the overall process:

Wrap up

There are still a couple of things left unsolved with these Webkeys, they have some addition exposed leads on the board that I'm pretty sure can be used to program the MCU, and I haven't figured out the hex representation all of the keyboard control keys the Webkey uses in it's EEPROM (it doesn't use standard keycodes). For instance, I know0xA8 is enter, 0xFF doesn't really do anything, and 0xA9 is escape - it would be nice to figure out the rest. Also, it looks like some data on the EEPROM gets cut off with longer strings. I think there is a setting in the MCU that defines how many characters it expects the URL to be- If I figure out how to reprogram the MCU, then hopefully I can change that.

Overall, these things have a big potential for a cool free Teensy-like device. They also have some seriously scarey implications if they're branded with a company logo and left in an open area like the booth of a conference.

Stay Tuned - In the next couple of months I'll be releasing a whitepaper that details the inner workings of these fun little devices even more!

What do you think? Free your mind in the comments below!