By Brad Antoniewicz.

Cisco's WebEx is a hugely popular platform for scheduling meetings. You can conduct video and voice calls, screen sharing, and chat through the system. Meetings are usually created via a Web Portal were the user defines when the meeting starts, how long it goes for, and what services (e.g. screen sharing or just voice) their meeting will leverage. WebEx also provides a One-Click Client that offers standalone meeting scheduling and outlook integration so that users can avoid the Web Portal.

The One-Click Client has the ability to save a user's password, so I decided to take a quick look at that functionality - in about an hour I was able to determine the storage, reverse the method it used to encrypt the password, and write a proof of concept tool to decrypt the local storage of the password. The aim of this blog post is to document that process and maybe encourage you to do some reversing!

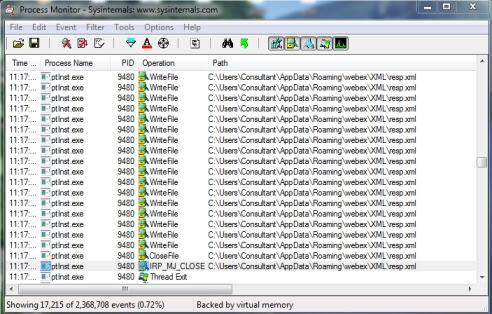

Process Monitor is one of those core tools that everyone should have handy and is perfect for this use case.

At this point in the process, we'll focus on One-Click's

First step is to create filter for the executable to reduce getting overwhelmed with information from other processes. Remove all existing filters and then create one to include all processes whose name is "

Next up, provide the application a username, password and URL, and tell it to save the password. As soon as the login button is clicked, Process Monitor will show a ton of activity. The first thing that catches my eye is that there are a bunch of writes to the

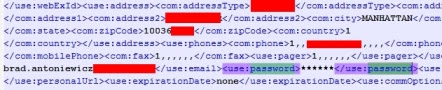

It's common for applications to store configuration information in an XML file, so maybe we'll get lucky with this one.

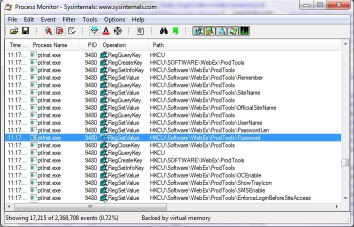

Next thing that may catch your eye is a number of queries to the Registry. It's very common to see application using the registry to store various information. These queries are particularly interesting because they contain the word "Password":

This is a pretty good indication that the password and password length are stored in the registry. To confirm, check the registry keys themselves. It turns out that the

At this point, we need to determine what the value of

If you search through the string list, you'll notice the registry key names aren't there. This is because by default, IDA will only show zero terminated ASCII C strings. We'll learn a little lower that our strings are passed to a Unicode Windows API function.

To show Unicode strings within IDA, right click the Strings tab and go to "Setup". Next select "Unicode" under "Allowed String Types":

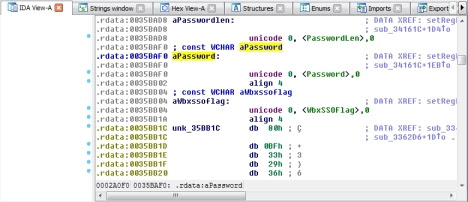

Scrolling through the Strings Window a second time will reveal the unicode encoded key name we're looking for: "Password". Double clicking it will open IDA View-A and bring us to the data segment in the binary where the string is located. You'll notice that right above the unicode entry, at the same address, IDA automatically gave this location a variable name, "

By selecting "

We just need to find where the registry key is either set or read and we'll likely see a call to some function nearby that decrypts it. The second reference,

If we look at the

So this means that it's likely the value being set for

The function call after a bunch of pushes is to

This means our

Function

Looks like they all line up. Also make note of the

And then there are calls to

To make life easier, I used WinDBG, set a breakpoint on the call, and inspected the memory at that location. What I discovered is that the key being used was a combination of these two registry keys:

For

Which led me to believe the key was essentially the

This is where that big constant value comes in. If you look at it fully assembled, you'll find that it is:

This gives us everything we need to encrypt the password, our psuedocode for the assembly in

You'll need to edit the source and manually define the appropriate values for

Hope you liked this, if so - Follow me on twitter - @brad_anton

Cisco's WebEx is a hugely popular platform for scheduling meetings. You can conduct video and voice calls, screen sharing, and chat through the system. Meetings are usually created via a Web Portal were the user defines when the meeting starts, how long it goes for, and what services (e.g. screen sharing or just voice) their meeting will leverage. WebEx also provides a One-Click Client that offers standalone meeting scheduling and outlook integration so that users can avoid the Web Portal.

The One-Click Client has the ability to save a user's password, so I decided to take a quick look at that functionality - in about an hour I was able to determine the storage, reverse the method it used to encrypt the password, and write a proof of concept tool to decrypt the local storage of the password. The aim of this blog post is to document that process and maybe encourage you to do some reversing!

Process Monitor

Usually the first step when evaluating client applications, is to get an understanding of what file system changes the application is performing (read/writes). This is especially true when you're looking for something thats being stored (in this case, the saved password) because stored info is usually written to a file, database, or within the Windows registry.Process Monitor is one of those core tools that everyone should have handy and is perfect for this use case.

At this point in the process, we'll focus on One-Click's

ptInst.exe executable. It's run during the initial install for One-Click and asks the user for username/password/server URL and if the application should save the password. With ptInst.exe running, we can launch Process Monitor.First step is to create filter for the executable to reduce getting overwhelmed with information from other processes. Remove all existing filters and then create one to include all processes whose name is "

ptinst.exe":Next up, provide the application a username, password and URL, and tell it to save the password. As soon as the login button is clicked, Process Monitor will show a ton of activity. The first thing that catches my eye is that there are a bunch of writes to the

resp.xml XML file. It's common for applications to store configuration information in an XML file, so maybe we'll get lucky with this one.

resp.xml does contain lots of data, but unfortunately there are 6 stars in place of the actual password (password length is greater than 6, fwiw). So back to Process Monitor.Next thing that may catch your eye is a number of queries to the Registry. It's very common to see application using the registry to store various information. These queries are particularly interesting because they contain the word "Password":

This is a pretty good indication that the password and password length are stored in the registry. To confirm, check the registry keys themselves. It turns out that the

HKCU\Software\WebEx\ProdTools\Password key stores some hex value that isn't the cleartext password, and HKCU\Software\WebEx\ProdTools\PasswordLen contains the length of password. At this point, we need to determine what the value of

HKCU\Software\WebEx\ProdTools\Password is. It's probably the password, but somehow obfuscated or encrypted and deciphering isn't obvious.IDA Pro

IDA Pro is another core tool. It's really the defacto tool for reverse engineering. Freeware and Evaluation versions are available and should be completely capable if you're following along (although I am using the paid version).Strings

Programs often contain constant string values to be used when performing certain functions. For instance,ptInst.exe will likely always use the same registry keys (e.g. HKCU\Software\WebEx\ProdTools\Password), so those actual strings should be stored somewhere within the binary. There are a number of programs that allow you to search for strings within a binary, we'll use IDA (View - Open SubViews - Strings): If you search through the string list, you'll notice the registry key names aren't there. This is because by default, IDA will only show zero terminated ASCII C strings. We'll learn a little lower that our strings are passed to a Unicode Windows API function.

To show Unicode strings within IDA, right click the Strings tab and go to "Setup". Next select "Unicode" under "Allowed String Types":

Scrolling through the Strings Window a second time will reveal the unicode encoded key name we're looking for: "Password". Double clicking it will open IDA View-A and bring us to the data segment in the binary where the string is located. You'll notice that right above the unicode entry, at the same address, IDA automatically gave this location a variable name, "

aPassword". By selecting "

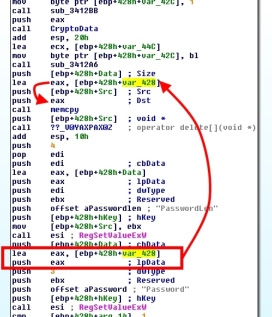

aPassword" and pressing the "x" key, you'll see all of the cross references to that variable name - This is everywhere its used in the program.We just need to find where the registry key is either set or read and we'll likely see a call to some function nearby that decrypts it. The second reference,

sub_34161C+1EB looks to be setting the value since a few instructions after the reference, a call to RegSetValueExW() is made. RegSetValueEx()

An observation to make is that the program is callingRegSetValueExW(). The "W" stands for "wide" which indicates the program is using the Unicode version of the RegSetValueEx() API function. This speaks to why we needed to configure our Strings Window to show Unicode strings. Had the function been RegSetValueExA(), we'd be using the ANSI version. If we look at the

RegSetValueEx()MSDN Page we see that the fifth value passed to the function is a pointer to the data which is to be stored within the registry key. IDA helps us out a bit by showing the same data types for each of the values being pushed onto the stack as the MSDN entry. Looking at the fifth value pushed onto the stack (working backwards from the call to RegSetValueExW()), we see lpData, which is stored within the EAX register. It's value is loaded into that register by the prodceeding call, where we find its actually the value [ebp+428h+var_428]. If we highlight that, then look at the previous references we'll discover that this value is always used above as the destination in an earlier call to memcpy(). So this means that it's likely the value being set for

Password registry key is the result of the memcpy(). We'll need to realign our trace to follow the source variable of that memcpy() if we want to figure out how our saved password is stored.To the Source

If we highlight theSrc to the memcpy(), or [ebp+428h+Src], we'll see its used above and pushed onto the stack:The function call after a bunch of pushes is to

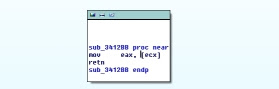

sub_3412bb. If we look at it, its a pretty simple function and doesn't really alter the stack :This means our

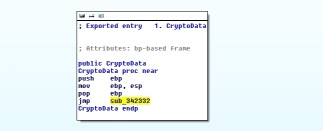

Src is still on the stack and may be used by the following function call to the CryptoData() exported function. CryptoData() sets up a stack frame and then does a quick jump to sub_342332:Function

sub_342332 starts to look interesting. First up, it has a bunch of arguments, this means that just by eyeing it up, we can guess that our Src will likely be used. If we count the number of elements pushed onto the stack, then look at the number of arguments IDA identified in the function, we could get an idea:Looks like they all line up. Also make note of the

cmp [ebp+arg_1c], 0. We can clearly see that the calling function sets that to 1, so we know that we'll be taking the negative branch on the jz below. Keys!

The negative branch brings us tosub_34227b which looks like gold. From a quick overview, we see that there is some constant value being loaded into an array or structure:And then there are calls to

AES_set_encrypt_key() and AES_ofb128_encrypt().A quick search will reveal both of these functions are part of the OpenSSL libraries. What's even better is that someone else has already implemented these functions in an open project. For whatever reason the OpenSSL documentation doesn't have full coverage of both of these functions, so this project helps to reduce the effort in guessing what the higher level code looks like and ultimately what's needed to reimplement it.AES_set_encrypt_key

First up I wanted to identify what values were being passed toAES_set_encrpyt_key(). I knew its arguments were something like: AES_set_encrypt_key (const unsigned char *someKey, const int size, AES_KEY *keyCTX)

To make life easier, I used WinDBG, set a breakpoint on the call, and inspected the memory at that location. What I discovered is that the key being used was a combination of these two registry keys:

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\WebEx\ProdTools\UserNameHKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\WebEx\ProdTools\SiteName

For

UserName I had braanton and for SiteName I had siteaa.webex.com/siteaa. When looking at WinDBG, the value being passed to AES_set_encrpyt_key() was: braantonsiteaa.webex.com/siteaab

Which led me to believe the key was essentially the

UserName value concantenated with the SiteName and repeated until it filled 32 characters (which accounts for the trailing "b").AES_ofb128_encrypt

A little searching revealed the arguments for AES_ofb128_encrypt should be something like: AES_ofb128_encrypt(*in, *out, length, *key, *ivec, *num);

This is where that big constant value comes in. If you look at it fully assembled, you'll find that it is:

123456789abcdef03456789abcdef012

This gives us everything we need to encrypt the password, our psuedocode for the assembly in

sub_34227b would look something like: IV = 123456789abcdef03456789abcdef012;

password = "some value";

key = [UserName + SiteName repeated to 32 chars];

num=0;

AES_KEY keyCTX;

AES_set_encrypt_key (key, 256, &keyCTX);

AES_ofb128_encrypt(password, out, sizeof(password), &keyCTX, IV, &num);

Decrypting

AES_ofb128_encrypt() uses output feedback (OFB) which makes the decryption process nearly identical to the encryption process. All we have to do is provide the encrypted value (i.e. the one stored in the Password key) with the appropriate length (i.e. the one stored in the PasswordLen key) and we'll be able to decrypt it. This all comes down to the static IV and UserName/SiteNamekey values. To demonstrate this, I wrote the following Proof of Concept code:You'll need to edit the source and manually define the appropriate values for

regVal and key then just compile and run: brad@wee:~/onedecrypt$ gcc -o webex-onedecrypt -lssl webex-onedecrypt.c

brad@wee:~/onedecrypt$ ./webex-onedecrypt

Reg Key Value = cc 6d c9 3b a0 cc 4c 76 55 c9 3b 9f

Password = bradbradbrad